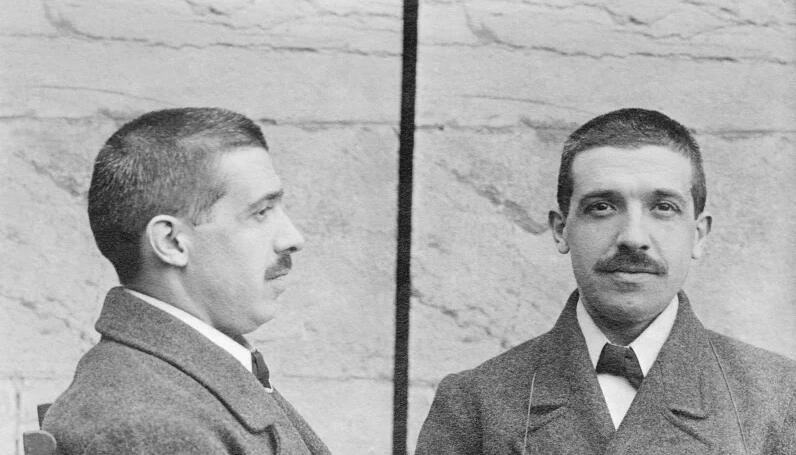

The scheme got its name from one Charles Ponzi, a fraudster who duped thousands of investors in 1919.

Ponzi promised a 50% return within three months on profits earned from international reply coupons. Back in the day, the postal service offered international reply coupons, which enabled a sender to pre-purchase postage and incorporate it in their correspondence. The recipient would then exchange the coupon for a priority airmail postage stamp at their home post office.

Due to the fluctuations in postage prices, it wasn’t unusual to find that stamps were pricier in one country than another. Ponzi saw an opportunity in the practice and decided to hire agents to buy cheap international reply coupons on his behalf then send them to him. He exchanged the coupons for stamps, which were more expensive than what the coupon was originally bought for. The stamps were then sold at a higher price to make a profit. This type of trade is known as arbitrage, and it’s not illegal.

However, at some point, Ponzi became greedy. Under the Securities Exchange Company, he invited people to invest in the company, promising 50% returns within 45 days and 100% within 90 days. Given his success in the postage stamp scheme, no one doubted his intentions. Unfortunately, Ponzi never really invested the money, he just plowed it back into the scheme by paying off some of the investors. The scheme went on until 1920 when the Securities Exchange Company was investigated.

Ponzi was brought down due to a series of investigative reports in the Boston Post newspaper, which ultimately led to a federal criminal investigation resulting in mail fraud charges.

Despite the notoriety of Charles Ponzi, the scheme that carries his name appears to have been first perpetrated by Sarah Howe in Boston in 1879, when she created the Ladies’ Deposit to help invest money for women. According to famed economist John Kenneth Galbraith, “the man who is admired for the ingenuity of his larceny is almost always rediscovering some earlier form of fraud.” As with Ponzi, Howe’s promises of profits were astounding, with promises that investors’ funds would be doubled in a mere nine months. Once again, it was journalists, this time reporters for the Boston Daily Advertiser, who investigated and discovered her scam. She was eventually charged and convicted of her crimes and served three years in prison. Upon being released, she managed to perpetrate an identical scam for two years before getting caught again.